Plotting Potter

One resource online that will never cease to amaze me is Project Gutenberg. From my friends in the political sciences to those in literature, and of course, data scientists … many have found what they seek on this website. Project Gutenburg is a collection of tens of thousands of classics 📚 and “cultural works” all available for free, utilizing books in the public domain. Its utility to other majors is understandable. The ease of access to the text is especially appealing to data analysts.

Remote I/O

Although there is a python library called Gutenberg available (check it out), I preferred the more traditional route. Py’s urllib quite a ‘raw’ way to get a remote resource. Incorporating a urllib.request will get us what we want. I chose to go with the requests module.

Make sure to use the url for the .txt version of a file on the website.

Processing

🐍

The end goal of such a task is to run any novel through the algorithm and the end result should be the names of the main characters in a novel. There are primarily two ways one can go about this.

Using Regex:

The following regex pattern was used to tokenize the entire text into ‘words’.

pattern = "['A-Za-z0-9]+-?['A-Za-z0-9]"

“Hello everyone. Welcome to” would be [‘Hello’, ‘everyone’, ‘.’, ‘Welcome’, ‘to’], when tokenized

Next, the text was split into bigrams. That would turn the above example to:

[ (‘Hello’, ‘everyone’ ), (‘everyone’, ‘.'), (’.', ‘Welcome’), (‘Welcome’,‘to’)]

For the entire text of the novel, we can next filter out all those bigrams which contain stop words. We can also retain ones in which both words start with capital letters. We can also include a regex pattern as shown below to include titles in our logic such as Dr. Mr. Mrs.

pattern1 = "[A-Z]+[a-z]{1,3}?[.]"

For Huckleberry Finn, our code would output this for the top 5 characters along with their count (v1) and independent character names (v2)

v1 = [(('Mary', 'Jane'), 41), (('Tom', 'Sawyer'), 40), (('Aunt', 'Sally'), 39), (('Miss', 'Watson'), 20), (('Miss', 'Mary'), 19)]

v2 = [('Jim', 341), ('Well', 318), ('Tom', 217), ('Huck', 70), ('Yes', 68)]

Similarly, name recognition for Harry Potter yields (some of the top ones):

v1 = [('Harry', 1217), ('Ron', 410), ('Hagrid', 336), ('Hermione', 257), ('Professor', 180)]

v2 = [(('Uncle', 'Vernon'), 97), (('Professor', 'McGonagall'), 90), (('Aunt', 'Petunia'), 51), (('Mr', 'Dursley'), 29), (('Harry', 'Potter'), 28)]

As we can see, the single names are not perfectly recognized and this is where nltk can be useful

Using nltk:

Using a nltk model trained on Gutenburg data for twitter streams would not give an accurate result since the language is outdated, however for this analysis it works. Using punkt corpus to tokenize the text and .ne_chunk for Named Entity Recognition, in very few lines of code, the following can be achieved for the top five.

v = [('Harry', 1247), ('Ron', 409), ('Hagrid', 255), ('Hermione', 228), ('Snape', 129)]

Plotting

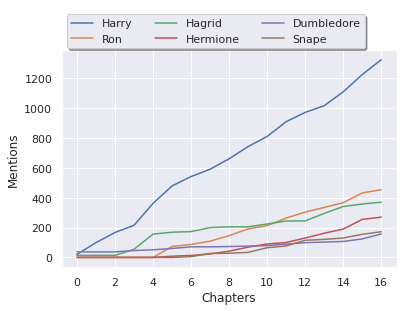

Before plotting, he book text needs to be split into chapters. This can be done quite easily since the chapter markings follow a repeated pattern. Next, for five of the characters, the cumulative occurrences through the chapters were counted and plotted.

It would be an interesting problem to think about how to find the occurances of Voldemort since he is a main character in the book, but appears by another name. 🤔

I would aikl to thank Prof. Michael Haberman for teaching a wonderful data science programming course.

Further Reading:

- What exactly is Named Entity Recognition?

- Different ways to tokenize text.

- A great resource for those interested in regex.